“As Urogynecologic/Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgeons, our armamentarium to repair the female pelvic floor has been significantly impacted by the recent removal from the market of synthetic mesh kits used for transvaginal repairs. As such, surgeons have searched for other options in order to achieve high success rates for prolapse repairs. Early results with the EnPlace system, during a postmarket clinical study, are encouraging as a minimally invasive, mesh-free and dissection free approach for pelvic floor procedures. The EnPlace system could be an excellent component (for those women who do not want or have tried a pessary) for the patient who desires a rapid and less restrictive recovery, or who cannot tolerate a prolonged procedure. We will continue to follow our patients, however EnPlace is becoming an important part of our POP treatment algorithm.”

G. Willy Davila, M.D. F.A.C.O.G.

Urogynecology/Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery Medical Director,

Women & Children’s Services at Holy Cross Medical Group Ft. Lauderdale, FL

There has been an escalating and spirited debate regarding the use of transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) reconstructive surgery.

The following synopsis provides a brief clinical history an background, to help explain the current landscape and important new (mesh-free) technology in the Women’s Pelvic Floor Health arena.

Data from three trials[2-4] compared native tissue repairs with a variety of total, anterior, or posterior polypropylene vaginal mesh kits for pelvic organ prolapse in multiple compartments. While no difference in awareness of prolapse was identifiable between the groups (RR 1.3, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.7) the recurrence rate on examination was higher in the native tissue repair group compared to the transvaginal polypropylene mesh group (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.1). The mesh erosion rate was 35/194 (18%), and 18/194 (9%) underwent surgical correction for mesh erosion. Assuming all the patients that underwent mesh erosion correction were the patients diagnosed with mesh erosion – these trials show that half of the patients who were diagnosed with mesh erosion required repeat surgery to resolve the situation. The reoperation rate after transvaginal polypropylene mesh repair of 22/194 (11%) was higher than after the native tissue repair (7/189, 3.7%) (RR 3.1, 95% CI 1.3 to 7.3).

In early 2016, the FDA increased its scrutiny into vaginal mesh implants and reclassified surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse as Class III, requiring submission of premarket approval (PMA) applications, the agency’s most stringent device review pathway. (Device classification depends on the intended use and indication of the device. Any potential risk from the device is a factor in class designation. Class I devices are low risk and Class III devices are greater risk.)

Also in 2016, a meta-analysis by Maher et al[6] was published in the Cochrane review. The paper reviewed 37 randomized control trials (RCTs) which represented n = 4,023 women. The authors concluded that, “While transvaginal permanent mesh is associated with lower rates of awareness of prolapse, repeat surgery for prolapse, and prolapse on examination than native tissue repair, it is also associated with higher rates of repeat surgery for prolapse or stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure (as a composite outcome), and with higher rates of bladder injury at surgery and de novo stress urinary incontinence. The risk‐benefit profile means that transvaginal mesh has limited utility in primary surgery. While it is possible that in women with higher risk of recurrence the benefits may outweigh the risks, there is currently no evidence to support this position.[6]”

The concern over pelvic floor mesh gathered global momentum. In November 2017, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) completed an extensive clinical review and concluded that the risks of pelvic floor mesh outweighed the potential benefits and removed the products for sale in Australia. Similarly, in December 2017, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines were published, recommending that mesh should no longer be used to treat prolapse in the UK. By July 2018, pelvic floor mesh was no longer available in the UK. This growing trend to eliminate products such as mesh, heavily impacts the millions of women (globally) who may benefit from pelvic floor treatment.

On April 16, 2019[7], the FDA ordered all manufacturers of transvaginal surgical mesh (for repair of anterior compartment prolapse (cystocele)) to immediately stop selling and distributing their products. The FDA determined that the manufacturers have not demonstrated reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for these devices.

In 2013, POP Medical Solutions, Ltd. began product development and conducted extensive cadaveric and engineering labs to answer the question, “Could pelvic ligament fixation be conducted with a small, single-incision, no mesh implant and no dissection?” That early development created the “NeuGuide” platform and a unique, novel surgical instrument was born. After preclinical cadaveric and animal trials showed promising results, a First-In-Woman (“FIW”) study was performed in Israel (n = 15), including post-hysterectomy patients (n = 6), which is a difficult population to treat. By 2016, the NeuGuide system received FDA clearance and, in 2018, after receiving CE Mark, a 15-site, global Post-Marketing Study was initiated to measure the results of this novel approach for pelvic floor ligament fixation[10]. In 2019, the company changed its name to FEMSelect, Ltd.

FEMSelect now introduces the revolutionary new system to provide Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgeons with an option for truly minimally invasive pelvic floor ligament fixation: The FEMSelect EnPlace.

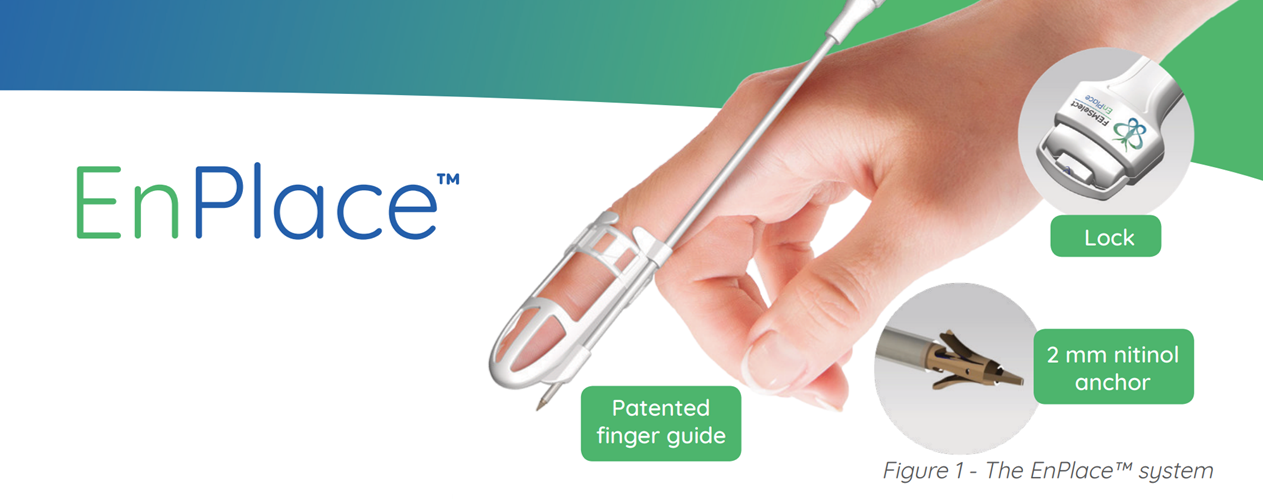

The EnPlace system is a meshless, truly minimally invasive anchoring device for attaching sutures to the sacrospinous ligaments with a small incision and no deep dissection. By utilizing a patented Finger Guide, which also provides a direct working channel for the surgeon –anchor placement can be both quick and precise. Since the working channel is part of the Finger Guide, the surgeon can rely on delivering an anchor to an exact location, every time.

Several studies were performed to validate and test the efficacy and durability of the EnPlace system (formerly called the “NeuGuide”).

In a preclinical study,[8] the pull-out force of the device was tested by performing measurements both on a porcine model and human cadavers. In the porcine model the mean pull-out force was 34.13±4.32 N. None of the measured forces were below 20 N (1 N is the force applied by 100 grams of weight to a surface it is placed upon), 35.68±9.28 N and none of the measured forces was below 20 N. No statistically significant difference was noted between the pull-out forces in the porcine and the cadavers (p=0.60).

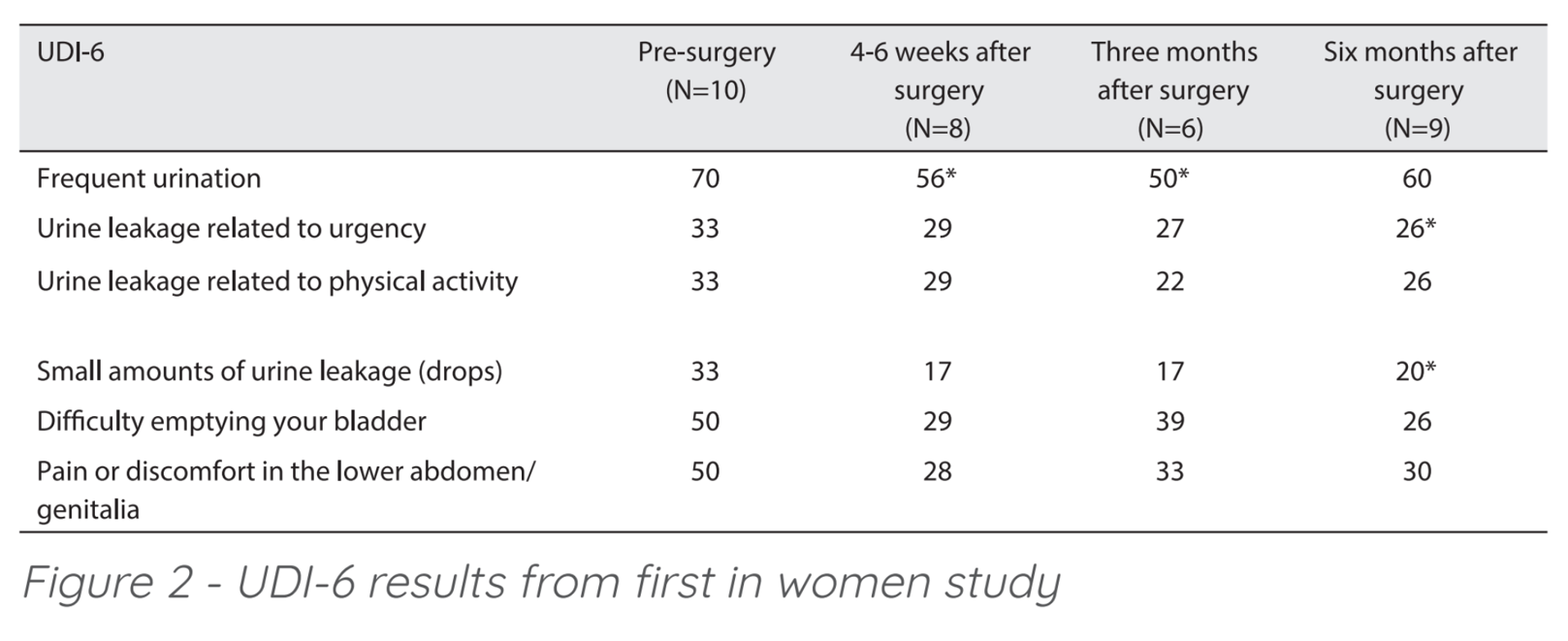

Results of the first 10 patients of the FIW study were published (Weintraub, et al 2017)[9] confirming EnPlace safety and efficacy. There was no injury to the bladder, rectum, pudendal nerves, or significant pelvic vessels and no febrile morbidity was recorded. At six months, results included 0/10 cases of centro-apical recurrence. Patients remain satisfied with the procedure and had favorable quality of life scores. The UDI-6 questionnaire (Urogenital Distress Inventory assesses symptom distress and quality of life in women suffering from urinary incontinence) was used to assess the quality of life of the patients and showed improvement in all domains. (Figure 2) Although the sample size was small, the improvement in urge and overflow incontinence related domains were demonstrated to be statistically significant.

Results of the first 10 patients of the FIW study were published (Weintraub, et al 2017)[9] confirming EnPlace safety and efficacy. There was no injury to the bladder, rectum, pudendal nerves, or significant pelvic vessels and no febrile morbidity was recorded. At six months, results included 0/10 cases of centro-apical recurrence. Patients remain satisfied with the procedure and had favorable quality of life scores. The UDI-6 questionnaire (Urogenital Distress Inventory assesses symptom distress and quality of life in women suffering from urinary incontinence) was used to assess the quality of life of the patients and showed improvement in all domains. (Figure 2) Although the sample size was small, the improvement in urge and overflow incontinence related domains were demonstrated to be statistically significant.

The initial 15 “FIW” patients are now out, nearly four- ears. The FIW investigators are diligently examining the follow-up data, intending to submit and publish the findings in a Peer Review setting. The “FIW” patients represent an important series to show the durability of the EnPlace fixation platform.

The 15-center, global Post-Market Approval study began in February 2018 – measuring success with 30 patients who required treatment for only uterine prolapse, to measure that the EnPlace system provides an acceptable approach for pelvic floor ligament fixation. Six-month data on the initial patients is very encouraging and the initial abstract was accepted for presentation to the combined AUGS/IUGA (American and International Urogynecologic associations) conference (September 2019). As the initial phase of the Post-Market study (n = 35) was completed, a second phase was developed to address more real-world patients who present with multiple pelvic floor symptoms and potentially requiring concomitant procedures for anterior/posterior repair or a mid-urethral sling for stress urinary incontinence. Coincidentally, the second phase of the study began approximately six-weeks before the FDA’s ruling to remove transvaginal mesh from the market. The expanded protocol allowed access to a larger patient population and subsequently, the second arm of the study (n = 30) will complete enrollment by August 2019.

The options for treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse have changed dramatically since 2011. The recent FDA ruling to remove transvaginal mesh from the Women’s Health arena is a significant change for both physicians and patients and yet, few options remain to help the millions of women who require treatment for this debilitating and often, painful condition.

The FEMSelect EnPlace stems from years of Urogynecologist-based development and provides a minimally invasive option for ligament fixation. The EnPlace™ is rapidly being evaluated as a potential leading option in the Women’s Health arena.

- Maher, C., et al., Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013. 2013(4).

- Withagen, M.I., et al., Trocar-guided mesh compared with conventional vaginal repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol, 2011. 117(2 Pt 1): p. 242-50.

- Iglesia, C.B., et al., Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol, 2010. 116(2 Pt 1): p. 293-303.

- Halaska, M., et al., A multicenter, randomized, prospective, controlled study comparing sacrospinous fixation and transvaginal mesh in the treatment of posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2012. 207(4): p. 301 e1-7.

- Maher, C., et al., Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2016. 11: p. CD004014.

- Maher, C., et al., Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. The Cochrane database of systematic

reviews, 2016. 2(2): p. CD012079-CD012079. - FDA, Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh Implants, https://www.fda.gov/medical- vices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-meshimplants.

- Tsivian, M., et al., Introducing a true minimally invasive meshless and dissectionless anchoring system for pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J, 2016. 27(4): p. 601-6.

- Weintraub, A.Y., et al., Safety and short term outcomes of a new truly minimally invasive meshless and dissection-less anchoring system for pelvic organ prolapse apical repair. Int Braz J Urol, 2017. 43(3): p. 533-539.

- https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03436979?term=neuguide&rank=